The site clusters together businesses working on innovative energy-from-waste technologies, including PowerHouse Energy - which turns plastic into hydrogen for powering buses and HGVs

Artist's impression of the Protos site, set up to be a generator of renewable power sources including transport fuel and hydrogen (Credit: Peel Environmental)

Turning waste into energy is the purpose of the Protos plant – an industrial eco-park being built in north-west England that could help solve the puzzle of how to find a use for unrecyclable rubbish.

The 134-acre site in Cheshire is equipped with innovative technologies that can recycle waste to create fuel used in vehicles and domestic electricity.

Construction work is ongoing but with a growing number of businesses operating in the new power-from-waste sector already clustered on site, NS Energy takes a look at what the £700m ($910m) project involves.

What is the Protos plant?

Located east of the town of Ellesmere Port on land between the Manchester Ship Canal and M56 motorway, the Protos plant aims to develop power from sustainable sources that have yet to be fully utilised in the energy mix, while preventing waste from going to landfill.

Examples include a factory that can convert unrecyclable waste plastic into hydrogen, and a plant that can turn wood and general waste into combustible gas.

The individual businesses running these operations are clustered together, and encouraged to share ideas and resources with each other.

The ultimate goal is to generate at least 140 megawatts (MW) of low-carbon heat and electricity each year, which could power more than 250,000 homes.

Waste infrastructure developer Peel Environmental – part of the Manchester-based real estate firm Peel L&P – owns the site, known as New Ellesmere Port, after buying it from energy giant Shell in the 1990s.

It received planning permission in 2009 after a public inquiry and construction began in late 2015.

Twelve of the 16 plots – measuring between 50,000 sq ft (4,600 sq m) and 350,000 sq ft (32,500 sq m) – have been completed and some are now occupied, with the development now on its second phase.

Peel claims it will create 3,000 jobs and pump £350m ($460m) into the north-west economy each year.

The project is a key pillar of the North West Energy and Hydrogen Cluster, which is backed by industry and regional mayors, as well as the North West Hydrogen Alliance, featuring Shell, Cadent and Mott Macdonald among its members.

Both have stated aims to make the region a national and global leader in low-carbon energy generation.

It’s estimated the cluster, which spans across the Manchester, Liverpool and Cheshire areas, could deliver 33,000 jobs, more than £4bn ($5.2bn) investment and save 10 million tonnes of carbon per year.

The focus on hydrogen reflects a general trend as it is a low-carbon gas that produces only water and heat when combined with oxygen, and can be used to power homes and transport.

Which waste-to-energy businesses are located at the Protos plant?

Bioenergy Infrastructure Group runs the Ince Bio Power plant, which is capable of generating 21.5MW of energy annually by converting wood waste into combustible gas.

It says this could save 65,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide each year – equivalent to taking 40,000 cars off the road.

Progressive Energy has agreed to move into one of the four plots still being built.

The clean energy company is working on a £150m ($195m) project to use materials such as unrecyclable wood and general waste to generate 175,000 tonnes of bio-resource gas that could power up to 1,000 low-carbon HGVs and buses every year.

It will be the UK’s first commercial-scale bio-substitute natural gas (bioSNG) plant when it begins production, expected to be in 2022.

Recycling company Advanced Sustainable Developments announced in April 2019 it planned to place its first UK plant at the Protos site.

The factory would use new technology to recycle PET plastic into food-grade material – something that can’t be achieved by current recycling practices.

One of the most intriguing companies on the cusp of joining the eco-park is engineering company PowerHouse Energy, which has developed technology that can turn plastic into hydrogen.

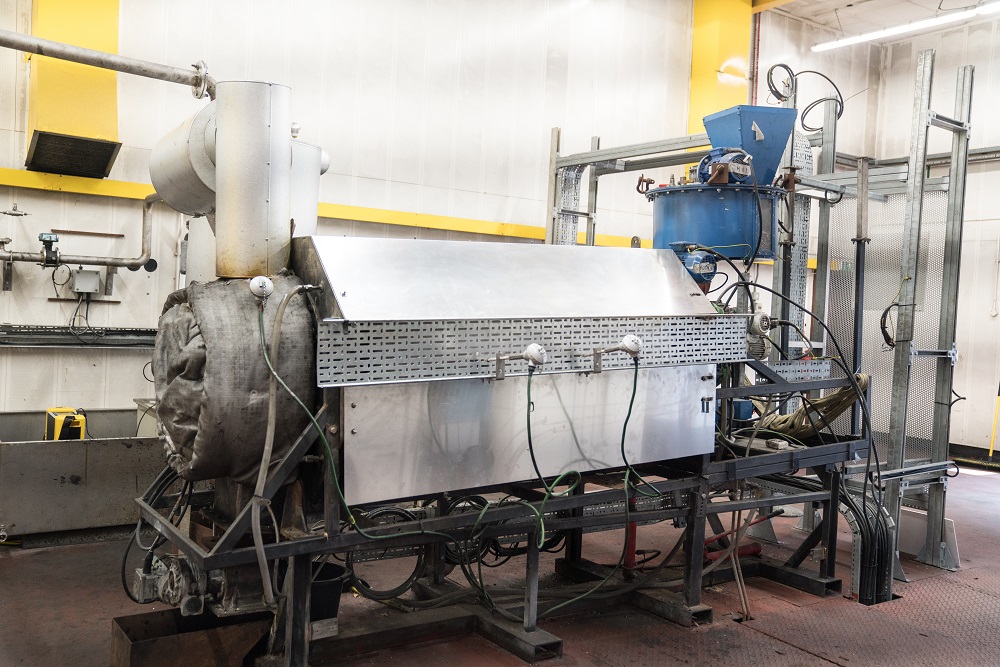

The West Yorkshire-based firm – which agreed to acquire its original partner in the energy-from-waste scheme, Waste2Tricity, in December 2019 – uses advanced thermal treatment technology to heat waste up until it is vaporised into gases.

Known as distributed modular generation (DMG), it controls the environment in the chamber to break down the resulting hydrocarbons and create fuel cells – electrochemical cells that convert chemical energy into electricity.

Tests have been carried out at the neighbouring Thornton Science Park – part of the University of Chester, which has linked up with Peel Environmental in the Protos scheme – and there’s hopes it could eventually turn 35 tonnes of unrecyclable plastic into 47 tonnes of gas and two tonnes of hydrogen each day.

Planning permission was granted by Cheshire West & Chester Council in March 2020 for the £7m ($9.1m) plastic-to-hydrogen factory, which will employ 14 people once it is built.

Future of the Protos plant – with plans for more UK sites

Peel Environmental believes the overall plan for the Protos plant, which has not yet been given a completion date, will require up to £1.5bn ($1.9bn) of investment.

Once construction work has been completed at New Ellesmere Port, there are plans to replicate the site in other parts of the UK as part of a wider strategy to reduce the environmental damage caused by plastic.

More than 300 million tonnes of the material are produced globally every year, with at least eight million tonnes ending up in the world’s oceans to make up 80% of all marine debris.

Many believe that, under current projects, the oceans will contain at least 937 million tonnes of plastic by 2050 — more than the estimated 895 million tonnes of fish by the same year.

In the UK alone, almost 1.2 million tonnes of plastic goes to landfill annually.

Peel Environmental managing director Myles Kitcher told NS Business the Protos plant was effectively a “shop window for a lot of start-up technologies”, with plans to commercialise those innovations and expand across the UK.

“The development will look different in different places, so you may not have an energy-from-waste facility, but the concept of having local energy generation is the whole thought process,” he added.

“The whole industry is moving away from big power stations. The whole of Europe’s doing the same, from big power stations in one location distributing the energy across a wide area to a more decentralised approach.”

PowerHouse Energy, along with the then-separate Waste2Tricity and Peel L&P, signed a collaboration agreement in August 2019 to build 11 plastic-to-hydrogen plants across the UK, representing an investment of £130m ($170m).

But the company has further projects in mind too and predicts the UK could eventually support between 100 and 200 sites – dubbed “plastic parks” – nationwide.

Announcing the deal, Kitcher said at the time: “Hydrogen is increasingly being seen as a vital part of our journey to zero carbon.

“This deal could be transformational in delivering a UK first technology that can generate local sources of hydrogen but also provide a solution to plastic waste.

“As a business, we’re looking at solutions for all plastics with a vision for these facilities to sit alongside recycling and recovery.

“We’re pioneering this solution in the North West but local authorities across the country could benefit from a more sustainable way to treat waste plastic, while also creating a local source of low-carbon transport fuel which could help them meet their climate change targets.”