Over the past decade, more than 50 coal companies have gone bankrupt and over 100GW of coal capacity has either retired or announced plans to retire

Trump said his administration would "take care of a lot of years of horrible abuse" towards the coal industry (Credit: Shutterstock/1427778647)

When Donald Trump was elected to the White House in 2016, he pledged to revive a US coal industry that was in seemingly terminal decline due to his predecessor Barack Obama’s stringent regulations on fossil fuels. But as new data shows power generation from the mineral fell to a 43-year low in 2019 and renewables look set to overtake coal production for the first time ever this year, James Murray explores what went wrong.

It’s just nine weeks after his unlikely election victory and Donald Trump is standing on a small stage at the offices of the Environmental Protection Agency, where he is making a special appearance to call for a review of the Clean Power Plan.

Behind him are stood more than a dozen coal miners, whose jobs he swears to protect from the red tape of green bureaucracy as he launches an executive order that could eventually lead to the repealing of his predecessor Barack Obama’s signature climate change policy.

At one stage, he points in the direction of Bob Murray, sitting in the front row. It’s a special moment for him, having been one of Trump’s biggest public supporters in the build-up to the polls.

His Ohio-headquartered company, Murray Energy, is the largest privately-owned coal firm in the US and the fourth-highest producer of the material in the country.

“Of course, it’s a human issue to me because my employees’ lives are being destroyed,” he will later say, recalling the event.

The 80-year-old has long advocated for government support for his industry — which employed about 80,000 people when the presidential baton was handed over but may have since halved during the Covid-19 pandemic — and was a strong critic of Obama, whose time in office he described as “eight years of pure hell”.

He told the Public Broadcasting Service’s 2017 Frontline documentary, War on the EPA, about how he met the then-Republican candidate at Trump Tower in New York City.

Detailing how it was just the two of them alone in the real estate tycoon’s office, he recalled: “We talked for 50 minutes — I can talk, he can talk — about coal, about the connection between coal miners’ jobs, coal miners’ families. I was so impressed with him.”

So having labelled Trump’s election success as a “wonderful victory”, the day Murray Energy filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in October 2019 was a key milestone in the downfall of coal.

Over the past decade, more than 50 coal companies have gone bankrupt and over 100 gigawatts (GW) of coal capacity has either retired or announced plans to retire as a drop in natural gas prices and a surge in renewables has inflicted a devastating blow on the fossil fuel’s future.

Dennis Wamsted, an analyst at the US-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), says coal’s importance will “continue to decline, as market erosion gains momentum across the industry”.

He points out how, in 2014, coal supplied 38.6% of the nation’s electricity needs, but that had dropped to 23.4% by 2019.

A report published by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) on 13 May projected this will drop to 19% in 2020, being overtaken by renewable energy for the first time with 20%. Nuclear at 21% and natural gas at 40% are also forecast to outstrip coal.

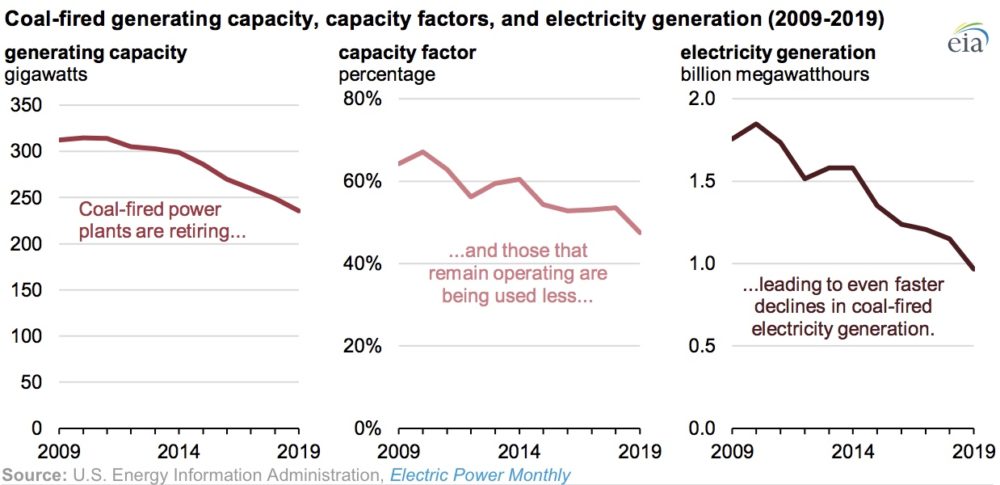

Further EIA figures reveal US coal-fired capacity peaked in 2011 and output from the fleet dropped to 966,000 gigawatt-hours (GWh) in 2019 — the lowest since 1976.

The 16% drop was the largest percentage decrease in history, while the 240,000 GWh fall was the second-largest drop in absolute terms.

Although the grim 2020 projection for the coal industry is largely blamed on the Covid-19 pandemic’s impact on falling energy demand — one analyst saying it has “put all the pressures facing the coal industry on steroids” — the 2019 data indicates it was already on its last legs.

“While it can be difficult to appreciate the speed of the decline of the US coal industry, the numbers speak for themselves,” adds Wamsted.

“Short-term economic uncertainty caused by the coronavirus pandemic and the recent collapse in oil prices may slow this transition slightly — but the trend is clear, coal is being driven to the brink by continued low gas prices and steady additions of wind and solar.”

What promises did Trump make to the US coal industry?

“Oh, coal country – what they have done… You are amazing people and we’re going to take care of a lot of years of horrible abuse – you can count on it, 100%… If I win, we’re going to bring those miners back to work – you’re going to be so proud of your president and your country. You’re going to be back to better than ever before and that means all kinds of energy. We never want to be in a position like we were in before, where we were literally controlled by people.”

It’s 5 May 2016 and Donald Trump is stood on another podium, this time at a Republican rally in Charleston, West Virginia, donning a miners’ helmet in front of thousands of workers — key voters who hold up signs reading “Trump digs coal”.

After being introduced to the soundtrack of John Denver’s state anthem Take Me Home, Country Roads, he promises to “put the miners back to work” and “get those mines open” in a long speech that comes two days after he won the Republican nomination ahead of his biggest rival Ted Cruz.

Trump capitalised on Hillary Clinton’s stance on coal

It highlights the stark contrast between the two candidates in the upcoming presidential election, as his rival for the Oval Office, Democrat nominee Hilary Clinton, had stated just weeks earlier that her government would “put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business” at a town hall meeting in Ohio — one of the country’s largest-producing states of the mineral.

This presents an opportunity for Trump to capitalise on, as just about any commitment to the industry is sure to secure a significant number of votes, something he is all-too-happy to exploit at the Charleston rally, deep in the Appalachian coal country.

The region, which stretches from the southern tier of New York State to the northern tips of Alabama and Georgia, made up about 26% of the nation’s coal production in 2018, according to the EIA.

Dr Themis Chronopoulos, an associate professor of American Studies at Swansea University, believes that, at some point, Trump “got the idea that when he went to rallies in certain places, people were so excited when he talked about coal”.

For many lifelong Democrats, either directly or indirectly employed in the energy industry, this marked a fork in the road as they swapped blue for red.

“Here, you have a guy that is saying he is going to support the coal industry and all the things they want to hear, and then there is the other person saying ‘well, I’m going to get rid of you’,” Dr Chronopoulos adds.

Although he believes Clinton did not intend to be so dismissive of fossil fuel industries and instead planned to invest in retraining workers, he acknowledges it broke down all relations with these voters.

Dr Chronopolous says the coal workers have “always been distrustful of the corporations that run the industry, and of Washington DC and politicians” — so, on the back of Trump’s promises, they figured ‘hey, here is this guy saying what we want to hear’.

Policies implemented by President Trump to try and revive the coal industry

Once President Trump was sworn into office in January 2017, Chronopoulos says his election cheerleader Murray began to “give ideas to the president about how he should reconfigure the environmental policy of the US” — a claim the coal magnate backed up in the Frontline documentary.

“I gave Mr Trump what I called an action plan very early,” he said.

“It’s about three-and-a-half pages of what he needed to do in his administration.”

Clean Power Plan

Number one on the list for Murray was to roll back on Obama’s Clean Power Plan (CPP).

The 2015 climate policy was designed to help lower carbon dioxide emitted by US power generators and aimed to reduce the sector’s emissions to 32% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Two months into Trump’s reign, the first steps were taken towards replacing the legislation.

Scott Pruitt, who was known for leading the fight against the previous government’s environmental regulations, had just been hand-picked by Trump as the EPA’s new administrator.

He said the president’s executive order would replace the plan with a “pro-growth approach”, as the administration believed it was a “job-killing regulation”.

In October 2017, Pruitt – who has since stepped down after being embroiled in an ethics scandal – signed a proposed rule to repeal the plan, a process that would take more than 18 months to complete due to federal regulatory procedures.

The CPP was brought to an end by his successor Andrew Wheeler in June 2019.

The EPA is still required to regulate emissions after the plan was replaced by the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule, which aims to cut power sector emissions by 11 million tonnes by 2030.

But the new legislation provides states with more time and authority to decide on how to implement technologies to reduce emissions from coal-fired plants and does not set any standards to cap those emissions.

The EPA said the new legislation, alongside “additional expected emissions reductions based on long-term industry trends”, is still expected to push emissions down by 35% over the next decade, while “providing affordable and reliable energy for all Americans”.

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, a non-profit international environmental advocacy group, economists predicted that by 2030, the CPP could have saved the US $20bn in climate-related costs and delivered between $14bn and $34bn in health benefits.

The council claimed, “the shift to energy efficiency and cleaner power” could also have reduced the average family’s electricity bills by $85 by 2030.

In contrast, the EPA projected that ACE would result in annual net benefits of between $120m and $730m, including “costs, domestic climate benefits and health co-benefits”.

The day after the ACE was implemented in place of the CPP on 19 June 2019, the EPA issued a press release featuring statements from 33 politicians and organisations.

It showed how some states believed scrapping the CPP would bring economic prosperity to industrial areas, with Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell calling it “just one more win for all the Americans who live and work in communities where affordable, homegrown American energy sources like coal still matter a lot”.

Tyler White, president of the Kentucky Coal Association, added in a June 2019 statement: “For a state like Kentucky, which produces nearly 75% of its power from coal, the CPP would have devastated the economic vitality of our state’s ability to produce affordable reliable energy.”

Liz Cheney, a member of the US congress for Wyoming — the largest coal-producing state in the country — said the ACE rule was an indication of how Trump’s administration was “once again working to strengthen the Wyoming economy and protect the energy industry by reversing the Obama-era CPP”.

She claimed the former plan was “killing jobs, strangling our economy, and slowly destroying our coal industry”.

“Ensuring the reliability of our electric grid by supporting coal — a crucial baseload power source — is an economic and national security priority,” she added.

“By returning more authority to the states, the ACE Rule will allow regulators in Wyoming and other states throughout the country to tailor their plans without the devastating effects of the CPP.”

Paris Agreement

When Trump committed to reviewing the CPP, members of the opposition and environmentalists became concerned about the US’s intentions towards fulfilling the pledge it made at the UN’s COP21 climate conference.

That was when the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement, an international pact signed by delegates of 196 nations, was signed.

Of all the countries to sign up to the treaty, the US was the second-highest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions behind China — making its commitment integral to combatting climate change.

Obama’s administration pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by between 26% and 28% from 2005 levels by 2025 — meaning they would have to be cut by about 1.7 billion metric tonnes.

EPA figures from 2017 revealed the nation was about a third of the way towards that target, with the CPP expected to play a key role in the reduction.

A 2017 report by the Climate Leadership Council (CLC), an international research and advocacy organisation, predicted emissions would be just over 400 million metric tonnes less than 2005 levels by 2025 if the CPP and other climate policies were rolled back.

After Trump made it clear that he intended to leave the alliance, there was a mixed response amongst the coal industry, according to a report by Virginia-based media outlet Politico.

The US’s top three coal producers at the time — Peabody Energy, Arch Coal and Cloud Peak Energy — indicated to White House officials they would not publicly object to the country remaining in the treaty should more investment be made available for “clean coal” carbon capture technology.

Although some of Trump’s administration were believed to be considering sticking to the pact, other figures within the fossil fuel industry were against it, with Murray referring to it as “illegal” and a waste of taxpayers’ money.

In November 2019, the president stated the Paris accord would “undermine the US economy” and put the country at a “permanent disadvantage” as the nation submitted a formal withdrawal notice, which will see the US leave the agreement on 4 November — a day after the 2020 election.

Other climate policy changes made by Trump

Chronopolous says Trump “got rid of some regulations that Obama implemented” and many others that already pre-existed him — making it easier for fossil fuel companies to operate.

One attempt by his administration came about in 2018, when energy secretary Rick Perry proposed to subsidise some nuclear and coal plants.

Murray was alleged to be part of the plan, which would have seen some of his customers benefit.

But a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, of which four of the five members were appointed by Trump, rejected the plans – a decision Murray admitted “did not sit well” with him.

Chronopolous believes the changes Trump has made to climate policies were “to an extent” to fulfil promises to the coal industry, but that the president had a “bigger strategy”.

“I think he wanted to make the US energy industry independent,” he adds.

“He succeeded in the sense that it is now producing — or was because now the price is too low — enough oil to not need to buy any from any other countries.

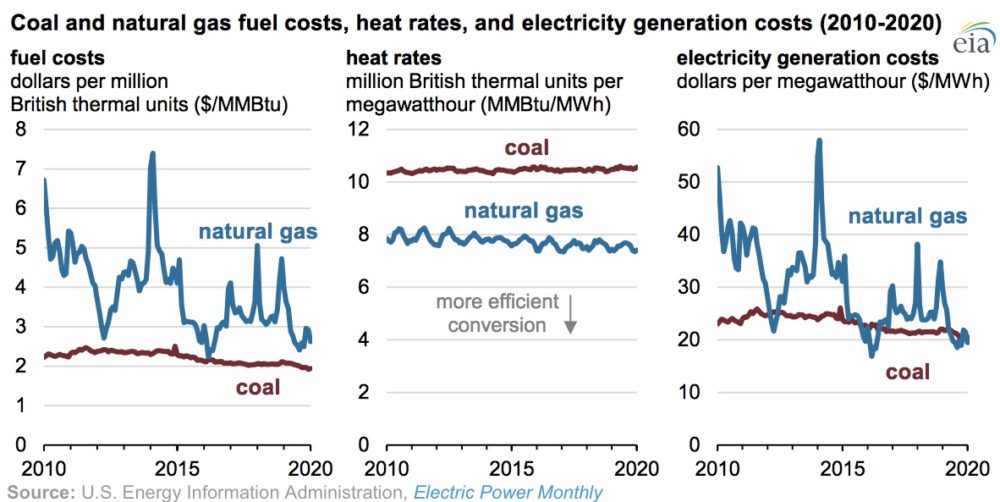

“The bad news about that is they didn’t use other sources, for example, natural gas is so much cheaper and cleaner — so why would you use coal?”

He points to a mistake Trump made during the trade war with China, an economic conflict which has been ongoing since 2018 after the US began setting tariffs and other trade barriers on China.

Chronopoulos highlights how previously the US would sell coal to China, which was “very good at targeting industries from states and counties supporting Trump”.

“Coal was one of those things” he adds.

“So, suddenly, they could not sell to China, which then decided to intensify its own production and not deal with the US.”

Chronopoulos says this affected some of the companies Trump had vowed to protect, and he believes the president “thought it was going to end and China would capitulate after three months”.

Is coal still a valuable source of energy?

Due to its “dirty” status, many countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have already started to distance themselves from coal — the world reduced its capacity by 8GW in the 18 months to June 2019, according to the NGO Global Energy Monitor.

Yet it still made up 38.5% of the global energy mix in 2018, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

That figure is largely due to consumption levels in China and India – the two most populated countries in the world.

Janet Gellici, CEO of the National Coal Council (NCC), a federal advisory committee to the US Department of Energy, believes coal is still valuable because “power grids benefit from reliable and resilient grids”.

She adds: “Coal power plants pose numerous repeatability and reproducibility (R&R) attributes that help stabilise the grid and power pricing, including fuel security, resource availability, on-site fuel supply, price stability and dispatchability, while emerging international economies need abundant, affordable resources.”

The NCC believes these R&R attributes need to be “assessed and valued” in the country’s energy portfolio and has recommended a four-step approach to the Department of Energy – to assess the value of the coal fleet; support efforts to retain continued operation of the existing coal fleet; reform the regulatory environment; and renew investment in coal generation.

Ashley Burke, senior vice-president of communications at the National Mining Association (NMA), the US’s mining trade organisation, says several states “rely on coal for the majority of their electricity generation” and coal generation has “played an outsized role in propping up the grid and providing reliability during extreme weather”.

Across the US, 687 million short tonnes of coal were consumed in 2018, according to EIA figures, accounting for 13% of the country’s total energy consumption.

The overwhelming purpose of coal production (92.6%) was for electric power generation — with the remainder used by industry, including steel-making, and transport.

“The fuel security and dispatchability inherent with the coal fleet can’t be easily replaced,” she adds.

“If you look at the states with higher percentages of coal generation, it shows that states with a diverse mix of fuels have some of the lowest prices per kilowatt-hour for retail electricity.

“When the economy is doing well, affordable energy may matter less to people.

“But throughout the coronavirus crisis, when Americans are losing jobs and businesses are struggling with basic cash flow — and even after, as the economy struggles to recover — keeping electricity bills low will be even more important.”

Burke says that aside from electricity generation, metallurgical coal is “key to steel production”, which is “critical to manufacturing and so many other industries”.

“One thing that has been exposed through the coronavirus crisis is the need to secure our domestic supply chains,” she adds.

“US coal is here and readily available to support a variety of industries.”

What is the current state of the coal industry in the US?

Bankruptcies, mine closures and coal plant retirements

When Murray Energy filed for bankruptcy in October 2019, it became the eighth US coal producer to do so in the space of 12 months, as the price of the fuel fell by 38% from a year earlier.

One of the latest casualties is Longview Power, which declared itself bankrupt on 14 April. Its financial troubles indicate the “increasingly dire state” of the country’s coal industry, according to IEEFA.

Longview’s primary asset is the 700-megawatt (MW) Longview Power Plant in Appalachian coal country near the city of Morgantown, West Virginia.

The IEEFA claims the plant has “much more going for it than most coal-fired plants in the US”, of which many are “far older, less efficient, and pay more to get their coal delivered”.

As it looks to shore up its long-term future, the bankrupt firm is now shifting its focus towards building a 1.2GW combined-cycle gas-fired facility and a 70MW utility-scale solar farm.

As for coal mines, following a drop in demand for the fuel, the number of active sites has plummeted from 1,435 in 2008 to 671 mines in 2017, according to the EIA.

The EIA’s data also shows that between 2010 and the first quarter of 2019, US power firms announced the retirement of more than 546 coal-fired power units — representing about 102GW of generating capacity and roughly a third of the coal fleet that was operating in 2010.

While 21 new units have opened across the nation over the past decade, the last of those to come online was the 106MW Spiritwood Industrial Park near Jamestown, North Dakota, in 2014.

But its owner, Great River Energy, announced in May 2020 that the station will be converted from lignite to natural gas in the near future.

The EIA’s analysis also highlights that “coal-fired units that retired after 2015 in the US have generally been larger and younger than the units that retired before 2015”.

It said the US coal units that retired in 2018 had an average capacity of 350MW and an average age of 46 years, compared with an average capacity of 129MW and an average age of 56 years for the coal units that retired in 2015.

Despite Trump’s efforts to revive the industry, more coal-fired plants were shut down in his opening two years in office compared to Obama’s entire first term.

Between 2009 and 2012, 14.9GW of coal power went offline, as opposed to 23.4GW between 2017 and 2018, according to the EIA.

After reaching a peak for shutdowns or conversions under Obama’s leadership in 2015 at 19.3GW, 2019 marked the second-highest year at 15.1GW.

Has the coal industry stabilised since Trump came into office?

In June 2017, Trump claimed at a rally in Iowa that he had “ended the war on coal” and was “putting the miners back to work”.

While figures from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the government’s principal fact-finding agency, backed up his claim that 33,000 mining jobs had been created (actual number 32,600) since his inauguration in January that year, it came with a caveat.

That’s because the mining category also included oil, gas extraction, quarrying and non-metallic mineral mining jobs – and just 1,000 of the additions were coal-based.

Then, at an August 2018 rally in Charleston, the president declared to the crowd “we are back – the coal industry is back”.

But in September 2019, Cecil Roberts, president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), said his message to Trump and others running for the presidency in 2020 was that “coal’s not back” and “nobody saved the coal industry”.

He added it was a “harsh reality” that coal-fired plants were closing all over the country.

Not that all blame can be directed at the incumbent of the Oval Office — indeed, Trump may never have been able to truly stem the flow.

The NCC’s Gellici notes four policy factors that have contributed to the closure of plants, many of which she claims were established under Obama’s administration and were either already underway or had been completed by the time Trump came into power:

- Regulatory requirements increasing costs of maintenance and operation

- Regulatory mandates requiring an increasing percentage of intermittent renewable energy (IRE) to be deployed by US utilities

- The EPA’s New Source Review discourages utility investments that would increase emissions in coal power stations

- Preferential treatment for IRE in funding support and regulatory treatment.

The NMA’s Burke believes many people have been either “too quick to dismiss or discount” the impact Trump’s administration has had in “reversing the almost cliff-like negative impact the Obama administration had on coal employment”.

She says employment plummeted from 134,000 in 2008 when Obama took office to 81,000 when he left in 2016 – a near 40% decline.

“In the first several years of this administration, the declines stopped and employment stood at just north of 82,000 for 2018,” she adds.

“Of course, the current situation in the electricity markets stemming from the coronavirus pandemic is one that no one could have anticipated and the long-term impacts are yet to be seen.”

The latest figures from the BLS suggests the nation’s coal-mining employment levels sat at 51,100 in January this year, before tumbling to 41,900 in April as IEA forecasts suggest energy demand will drop 9% in the US and 6% globally this year.

US coal consumption plunging at the fastest rate since the Eisenhower era

Plant closures led to the largest decline in American coal consumption since former president Dwight Eisenhower’s era 65 years ago, Bloomberg reported in March.

In 1954, coal usage dropped by 14%, only to rebound by 15% the following year.

Total consumption slumped from 688 million short tonnes (MMst) in 2018 to 596MMst in 2019, according to the EIA — marking a 13% decline.

But the industry shouldn’t expect an Ike-like comeback this time around, with a further 13.3% drop to 516MMst predicted for 2020.

The declining coal consumption dovetails with falling output. The EIA cites the 16% decline in coal generation to 966,000GWh last year — representing the largest ever percentage drop and lowest production level, respectively — to several factors.

“Although lower electricity demand in 2019 was partly responsible for less coal-fired generation, the primary driver was increased output from natural gas-fired plants and wind turbines,” the EIA added in a report published on 11 May.

Natural gas-fired generation reached an all-time high of nearly 1.6 million GWh in 2019, up 8% from 2018. Electricity generation from wind turbines also set a new record, surpassing 300,000 GWh, up 10% from 2018.

Is the US coal industry salvageable or is it already too late?

Renewables could outpace coal this year

Market forces have contributed to both coal’s loss of supremacy and the upturn in fortunes for renewables and natural gas.

Solar costs have fallen by more than 80% since 2010, while the cost of building large wind farms has dropped by more than 40% — and the price of natural gas has fallen to historic lows because of the fracking boom, according to various US energy agencies.

The changing energy mix is illustrated by the latest data for the EIA as it predicts renewables to overtake coal for the first time at 20% and 19% shares respectively.

It marks a huge decline from the 39% contribution of coal just six years ago — the same year the final coal-fired power plant came online in Jamestown, North Dakota.

Dams, wind farms and solar panels have already generated more electricity than coal on 90 separate days this year — easily eclipsing the 2019 record of 38 days over the entire 12 months.

And with the EIA expecting a 5% drop in electricity production due to falling demand stemming from businesses closing and factories scaling back amid Covid-19 lockdowns, the need for coal and its high operating costs recedes even further.

Alongside the projections, IEEFA data shows a very tangible decline already this year for the fossil fuel.

In January, coal made up 19.9% of the market share for electric power generation, with renewables sitting at 17.6%.

A month later, coal had dropped to 18.3% and renewables rose to 19.7%, while preliminary estimates for March noted a 17.3% share for the mineral and 19.9% for clean energy.

Although April is typically a low generation month for coal because plants are taken offline for maintenance, compared to it being a relatively strong month for renewables, the figures remain damning for the coal industry.

Data recorded up until 24 April noted a 15.5% share for coal, while renewables came in at 21.7%.

IEEFA analyst Wamsted says: “15.5% is probably a record-breaking low for coal — it’s certainly a record-breaking low in the 30 years that I’ve been following the industry.

“It’s also a record-breaking percentage for renewables. These trends have been going in opposite directions for the past four months, but they have also clearly been going in opposite directions over the past five to 10 years as well.”

But this decline isn’t just being felt across the US, as global demand for the fuel in 2020 is set to experience the largest drop since the Second World War at 8%, while coal-fired generation is expected to fall by more than 10% this year, according to the IEA.

Do exports offer any chance of redemption for the US coal industry?

In 2019, about 14% of total US coal production (6% of thermal coal and 8% of metallurgical coal) was exported to at least 50 countries, according to the EIA.

And it’s the export market that may provide a glimmer of hope for the mining sector, with Asia the most likely destination.

While the rest of the world reduced its coal capacity by 8GW in the 18 months to June 2019, China increased its stock by 42.9GW, according to the NGO Global Energy Monitor – which predicts the gulf between the Asian superpower and other countries will only widen.

Meanwhile, coal-powered electricity has risen in India from 68% in 1992 to 75% in 2015.

The neighbouring South-east Asia is one of the few regions where the share of coal in the power mix increased in the IEA’s most recent figures for 2018 as new plants continue to come online.

The NMA’s Burke says the industry is “optimistic about the East Asian market”, where there are “both new coal-based power plants and industrial growth supporting future demand”.

“The Asian coal fleet is young — the average plant is just 11 years old — and new generating capacity is being added at a rapid clip,” she adds.

“Japan, for example, is adding 22 new plants in the next five years. Coal is a reliable, inexpensive and secure fuel that continues to underpin energy security and industrialisation in developing as well as developed economies.

“An additional factor in our favour is that bulk carrier freight rates are coming down due to low petroleum prices. It makes exporting coal less expensive.”

But exports, already accounting for a relatively small proportion of production, are expected to take a hit this year.

Data recorded by S&P Global Market Intelligence shows that up until 22 February, the amount of coal exported by the top five US ports declined by 69% year on year.

Change in president ‘bodes ill for coal’

If the outlook for coal didn’t look particularly bright under Trump, the picture could be even gloomier should Democratic candidate Joe Biden win the 2020 election.

Although questions remain about his climate change credentials, the 77-year-old is a keen environmentalist compared to the current incumbent of the Oval Office.

He has pledged to improve the carbon performance of the US, which has already reported emissions falling by 15% since 2005 due in part to coal’s decline. The EIA predicts they will fall 11% this year alone, the biggest drop in 70 years.

During a campaign event in December 2019, he suggested coal miners could simply learn to code to transition to “jobs of the future”, Newsweek reported.

Biden, who served as vice-president under Obama, claimed that “anybody who can go down 300 to 3,000 feet in a mine, sure in hell can learn to programme as well, but we don’t think of it that way”.

At another campaign event the same week, he told the audience about his plans to eliminate fossil fuels, including coal.

He added that he would hold executives accountable for using fossil fuels and would “put them in jail” if they didn’t comply.

But for voters praying for Trump to earn a second term in office, IEEFA data analyst Seth Feaster warns a lot of his policy initiatives to try and support the coal industry have “really had very little to no effect”.

“Coal is really falling fast and most of the policy initiatives didn’t really work out and were not implemented well – and they didn’t really help the coal industry much at all,” he adds.

“It bodes rather ill for the coal industry if there is a change in party in the White House come the fall.

“Because if coal can’t survive under probably one of the most coal-friendly administrations in a long time, then I’m not sure it’s going to do that well if the party changes.”

Trump and coal: A pointless war?

Back on the EPA stage with the workers alongside him and Murray in the front row, Trump makes a big promise to the mining industry.

“The miners told me about the attacks on their jobs and their livelihoods,” he says.

“They told me about the efforts to shut down their mines, their communities and their very way of life. I made them this promise. We will put our miners back to work.

“My administration is putting an end to the war on coal.”

Unfortunately for the president and coal miners, it could be the battle had been lost a long time ago.